In Defense of Machine Politics

- Janus Editorial Board

- Apr 8, 2018

- 3 min read

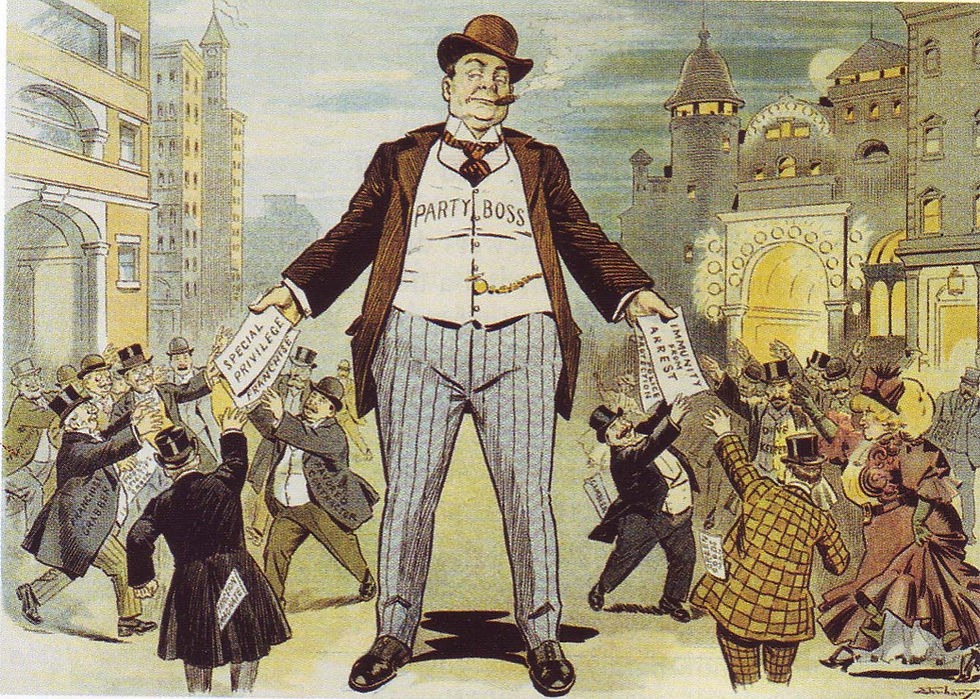

In canon of American political history, the urban political machines of the late 19th – early 20th century often rank among as one of the lowest forms of American politics. In popular imagination, the political machine serves as the boogeyman. Images of smoked-filled back rooms in over-industrialized cities invite conspiratorial comparisons to secret cabals and greedy and ambitious politicos. However, such a negative remembrance of the individual particulars of the political machines disregards the disparate positive influences that they had on American politics for much of the 20th century.

A defense of the political machines must be couched in the realities of their excess. The machines were corrupt, racist, criminal, violent, and self-serving. It is for the best that their prominence has faded from American political life and that large populations are not under the grips of a few concentrated individuals. With that, it is necessary to understand how the machines reshaped American politics in a positive manner. It is also necessary to place their development within the historical development of the United States.

Machine politics had a temporal anchor. In the aftermath of the Civil War and the rapid influx of new immigrants, the traditional political structure – landed elites with strict sectionalist ties – was not sustainable. By the 1870s, and continuing through the end of the century, the new political landscape required a new political structure, and, in the cities, this structure was the machine. Political machines served as the ultimate expression of party politics. Structurally, party officials defined territories within the city, organized various ethnic populations, and hired a fleet of workers to ensure cooperation and fidelity to the party. Electorally, party officials slated candidates, squashed disloyalty, rewarded quid pro quo, and deindividualized politics. Socially, party officials provided jobs, welfare, a sense of community and homes to their supports. They also integrated new immigrant arrivals into existing communities. Taken as a whole, the party officials – through these structural, political, and social actions – helped build organized, interdependent communities that helped new Americans feel less lost in the new world. This social benefit has long reaching implications. The organization of immigrant communities in the decades after the Civil War helped pave the way for progressive reforms, the New Deal coalition and even the organization of the rights-consciousness movements

of the 1960s. As anti-democratic as the machines were, they inspired a longing for democracy. As reformers challenged the machines they called for a more democratic system; thus, good democratic reforms began as opposition ideas.

Machines also made politics local, personal, and fun. The parties made sure that people were happy members, at least on a superficial level. It is fun to be part of the club, to have a (small) say in public affairs, and to feel that you influence your political life. Politics became a sport, with various local characters rising and falling spectacularly. A hallmark of a healthy democracy is an involved and excited populace. While the excitement grew into frustration at the end of the 19th century, this frustration was only possible because people had so long been involved in city politics.

Personally, I feel that politics ought to be a fun and exciting endeavor for all citizens. We are lucky enough to live in a (mostly-functional) democracy. American politics, at its best, is the American community unifying around ideas that are popular and ameliorative, exciting and good. Thus, American politics is at its best when people feel that they matter. While I think that we have yet to reached the zenith of this idea – too many people face systemic disenfranchisement – the arc of American history is and ought to be bending in this direction. The machines played an important and positive role in this development. They organized society and invigorated political life. Certainly, they were corrupt and greedy, but they set an admirable tone for political involvement, even if it was just a tone. Today, let us sardonically and good-humoredly remember their unique brand of democracy and challenge ourselves to achieve all that they could have been.

Comments