The Occupation of Alcatraz

- Amy Kurian

- Dec 11, 2023

- 4 min read

54 years ago this November, Native American activists occupied Alcatraz Island off the coast of San Francisco. In fact, there were three separate occupations of the island in 1969, the most notable of which started on November 20th and lasted until 1971. [1] Written in their proclamation entitled “Proclamation to the Great White Father and All His People,” the activists stated: “We, the native Americans, re-claim the land known as Alcatraz Island in the name of all American Indians by right of discovery.” [2]

These occupations were not random acts. Rather, they were just one part of the growing “Red Power movement” of the 1960s. During the years leading up to the occupations, the Indian Relocation Act of 1956 “promised relocation to a major urban area, vocational training, assistance in finding jobs, adequate housing, and financial assistance.” [3] As a result, many Natives were relocated to the Bay Area. The influx of a new Native urban population led to the creation of social organizations, but also a sense that the government had abandoned them. The relocation program was unsubstantial: the financial assistance and job assistance were extremely minimal, job training often only lasted three weeks as opposed to the promised three months, and the provided housing was in run-down, impoverished areas. [4]

The first occupation of Alcatraz occurred on March 8th, 1964, when around 40 people occupied the island. As the basis for occupation, the group referred to the Sioux Treaty of 1868 which “implied that vacated federal lands could be occupied by American Indians.” [5] Although this attempt only lasted for four hours, this sentiment continued to the following occupations of the island.

The November occupations were led by a group that called themselves “Indians of All Tribes”. The second occupation occurred on November 2nd, with Mohawk activist Richard Oakes often referred to as the leader. This attempt lasted for the night, but the same group returned on November 20th “with an occupation force of 89 men, women, and children.” At its peak, the island had more than 400 occupants, many of whom were Native American college students. [6]

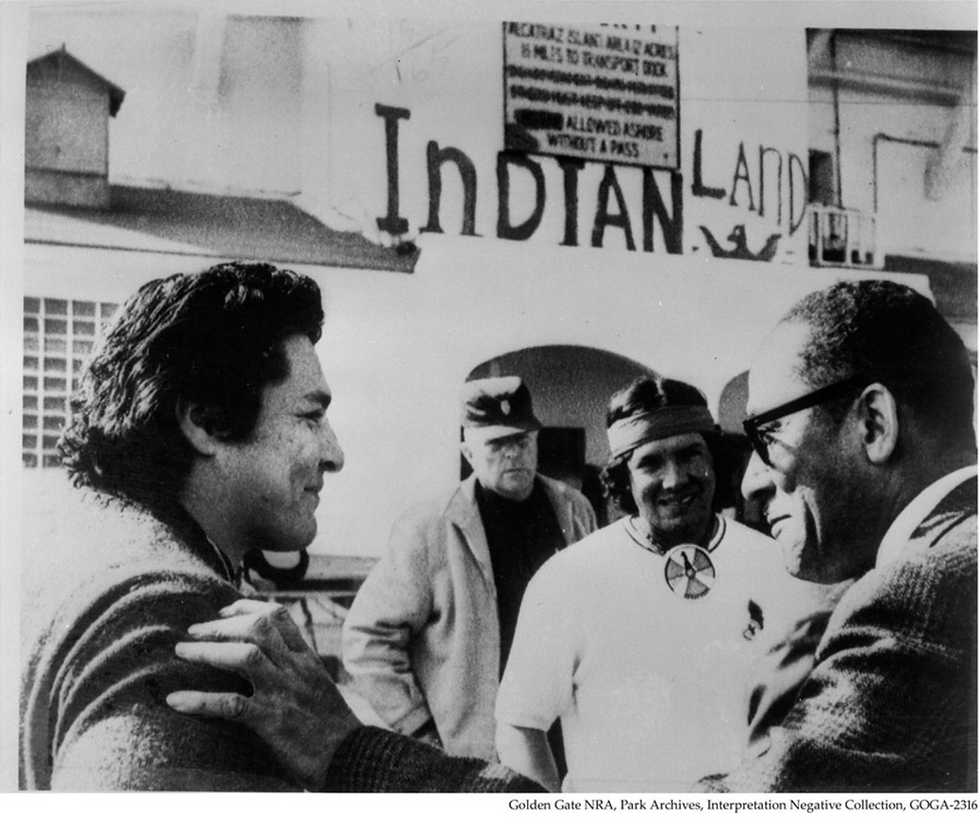

Richard Oakes (left) shortly after the beginning of the occupation

Alcatraz Island itself was used as a symbol of Native American oppression. In their proclamation, the activists sarcastically compared the island to reservations suitable for living “as determined by white man’s own standards.” As in, “It is isolated from modern facilities, and without adequate means of transportation. It has no fresh running water. It has inadequate sanitation facilities. There are no oil or mineral rights. There is no industry and so unemployment is very great…” and the list continues. [7]

Native Americans used the concept of self-determination as a means of empowerment. The Indians of All Tribes formed their own governing council on the island, as well as a “clinic, kitchen, public relations department, and even a nursery and grade school for its children.” [8] The group also created their own forms of media, such as the Alcatraz Newsletter and the broadcast Radio Free Alcatraz. Not only did the occupation receive national attention, but it also received many donations in the form of canned food, clothing, and money.

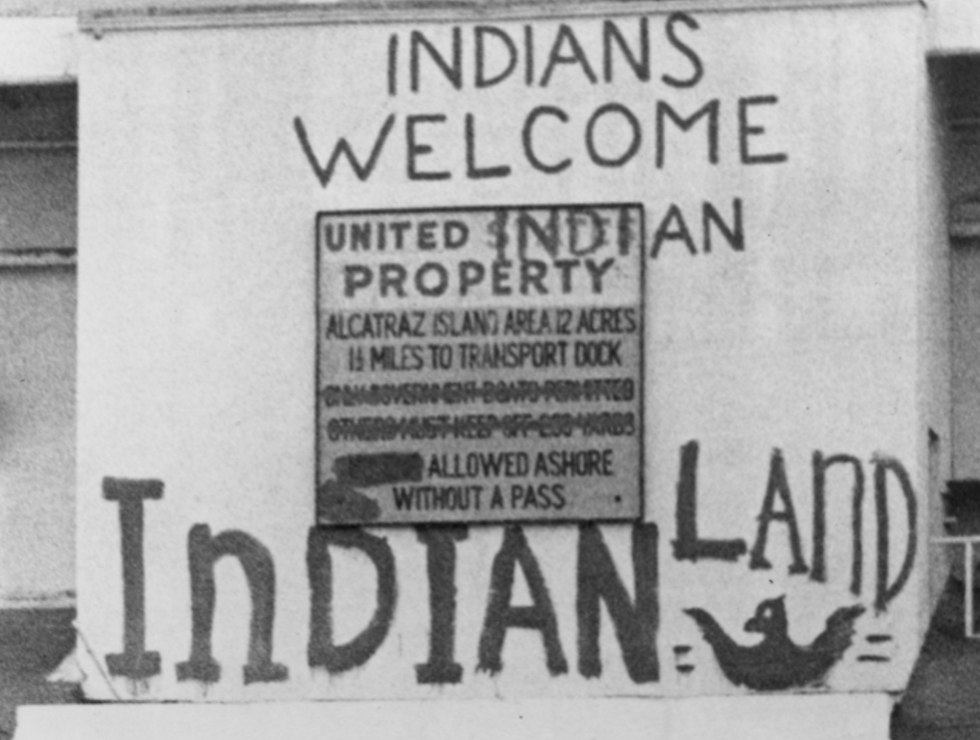

Activists standing in front of a changed sign

Conditions on the island began to worsen into the 1970s. Many occupants left the island, especially as college students returned to school. Additionally, two opposition groups formed on the island against Richard Oakes. Oakes himself would leave Alcatraz in 1970 following the accidental death of his stepdaughter. Then, the Nixon administration cut off power and water to the island, and a fire broke out three days afterward. [9] The occupation officially ended on June 10th, 1971, when “armed federal marshals, FBI agents, and special forces police swarmed the island and removed five women, four children, and six unarmed Indian men,” the last remaining people on the island. [10]

Despite its unfortunate end, the November 20th occupation was a cornerstone of the Red Power movement, especially as it set the precedent for future activism. Similar occupations occurred following its end, like the activist takeover of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1972 and the Wounded Knee Occupation in 1973. Overall, “some 50 other occupations took place across the country” after 1971. [11]

The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act was passed in 1975, allowing Native Americans to have more autonomy and management over their affairs. The occupation of Alcatraz and Red Power activism contributed to the end of the “termination era” of Native American policy. As activist Adam Fortunate Eagle said in a 1971 interview, “The purpose of occupying Alcatraz was to start an Indian movement and call attention to Indian problems… It has served its purpose.” [12]

Notes

[1] Evan Andrews, “When Native Americans Occupied Alcatraz Island,” History, July 11th, 2023. https://www.history.com/news/native-american-activists-occupy-alcatraz-island-45-years-ago

[2] Adam Fortunate Eagle, “Proclamation to the Great White Father and All His People,” November 20th, 1969. https://muscarelle.wm.edu/rising/alcatraz/proclamation/

[3] Troy Johnson, “The Occupation of Alcatraz Island: Roots of American Indian Activism,” Wicazo Sa Review 10, no. 2 (Autumn, 1994): 65.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Victoria Juarez, “AIM & the Occupation of Alcatraz Island,” Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II 22, no. 7 (2017): 21.

[6] Andrews, “When Native Americans Occupied Alcatraz Island.”

[7] Adam Fortunate Eagle, “Proclamation.”

[8] Andrews, “When Native Americans Occupied Alcatraz Island.”

[9] Troy Johnson, “We Hold the Rock.” National Parks Service, November 28th, 2019. https://www.nps.gov/alca/learn/historyculture/we-hold-the-rock.htm

[10] Ibid.

[11] Johnson, “The Occupation of Alcatraz Island,” 75.

[12] Adam Fortunate Eagle, Interview with newspaper, San Francisco Chronicle, April 1971.

Bibliography

Adam Fortunate Eagle, “Proclamation to the Great White Father and All His People.” Proclamation, November 20th, 1969.

San Francisco Chronicle. Interview with newspaper, April 1971.

Andrews, Evan. “When Native American Activists Occupied Alcatraz Island.” History.com, July 11, 2023. https://www.history.com/news/native-american-activists-occupy- alcatraz-island-45-years-ago.

Johnson, Troy. “The Occupation of Alcatraz Island: Roots of American Indian Activism.” Wicazo Sa Review 10, no. 2 (1994): 63–79. https://doi.org/10.2307/1409133.

“We Hold the Rock.” National Parks Service, November 26, 2019. https://www.nps.gov/alca/learn/historyculture/we-hold-the-rock.htm.

Juarez, Victoria. “AIM & the Occupation of Alcatraz Island.” Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II 22, no. 7 (2017): 21-29. https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/historical-perspectives/vol22/iss1/7.

ImagesGolden Gate NRA. “Richard Oakes on Alcatraz.” National Park Service. Photograph. https://www.nps.gov/media/photo/gallery.htm?pg=431309&id=8ED62F03- 155D-4519-3E4A2F88E55F84CB.

Maggiora, Vince. “Indian occupiers change the sign from US to Indian on Alcatraz.” Photograph. https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Alcatraz-s-American-Indian-past- refreshed-7004146.php.

Unknown Photographer. “During the Occupation.” FoundSF. Photograph. https://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=The_Indian_Occupation_of_ALCATRAZ.

When shopping for a Mens Western Jacket, it's important to find one that balances authentic western style with modern comfort and fit. The right jacket should feel both timeless and personally yours. Western Jacket excels at this balance.

The Stylish Men’s Leather Motorcycle Jacket combines sleek modern design with robust functionality, making it perfect for both riding and casual wear. Crafted from high-quality leather, it offers excellent durability, comfort, and protection, while its tailored fit and refined detailing ensure you look sharp on and off the bike.

Shop Halloween Apparel to find the perfect mix of spooky, stylish, and comfortable pieces for the season. From festive hoodies and graphic tees to themed jackets and accessories, these outfits let you embrace the Halloween spirit whether you’re at a party, trick-or-treating, or just enjoying autumn vibes.

Shop now at Arsenal Jackets and experience the perfect union of style and ease with the Pink Gap Hoodie. Ready to turn heads and boost your confidence, this hoodie is more than just apparel it’s your statement of bold simplicity. Don’t miss out on making pink your new power colour.

Catch the wave with 50+ quantitative research proposal topics from the experts at https://www.phdresearchproposal.org/quantitative-research-proposal-topics/! If you want to excel, you can also write research proposal online with guidance from their professional team. PhDResearchProposal.org is a fantastic resource to spark ideas and achieve academic excellence faster and easier!